This is 50,000 BC all you know is 1 stick and 1 stick = 2 sticks. Tomorrow you will realise . But is hard, too many sticks. And that’s why we invented Computers.

We use mathematics to understand the world as an equation that has variables and constants. A program can be said as a sequence of equations, or operations, that transform inputs to desired form. Then computing is merely execution of a program on a machine, an abstract machine. Read this overview. When in a particular state, if a machine can only proceed one way it is called a deterministic machine else it is called non-deterministic. Ultimately any kind of rules based system is an abstract machine, and as developers we keep encapsulating machines inside other machines, see this. All real computers like your phone, washing machine, laptop are physical realisations, in an imperfect world, of these machines.

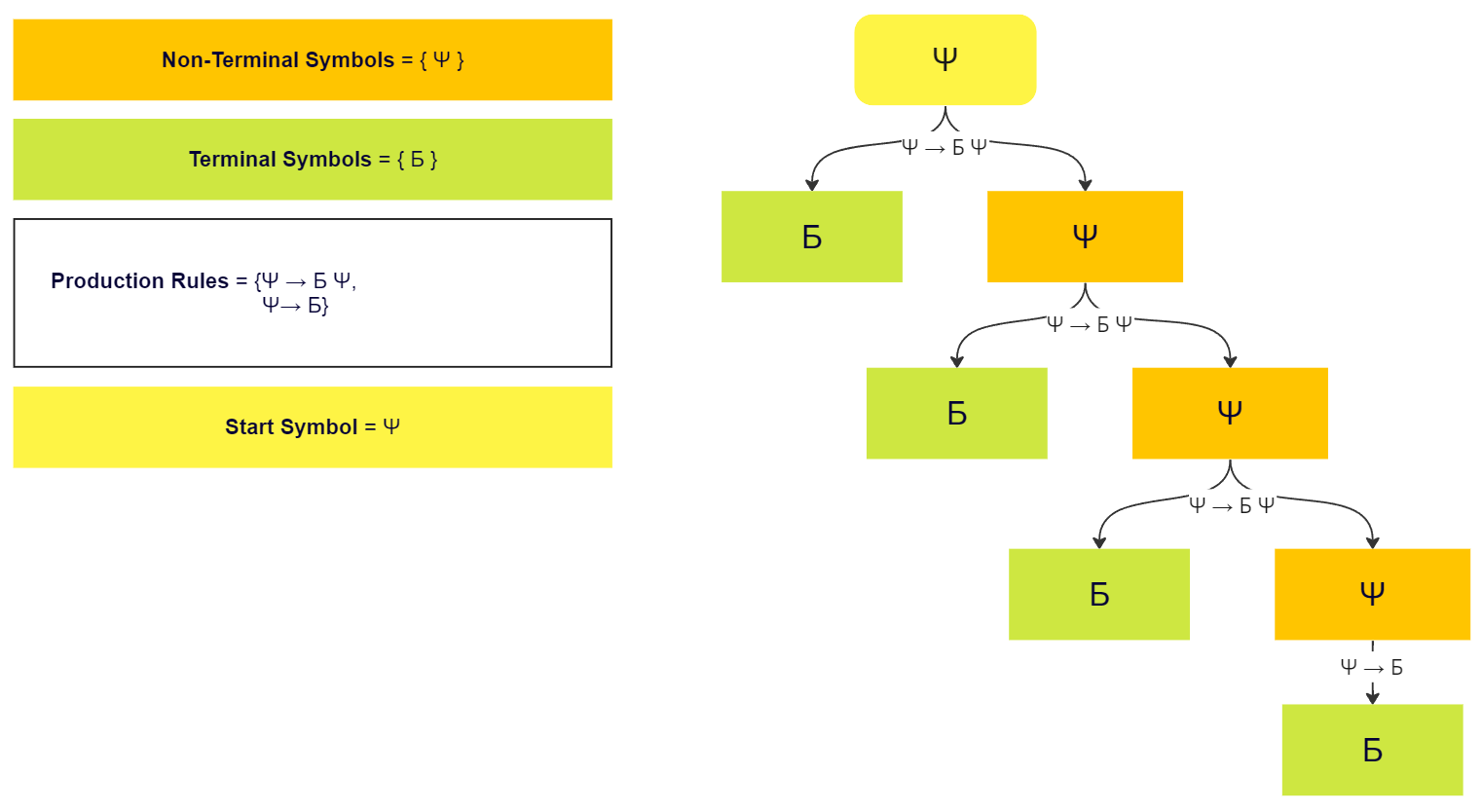

As programmers we are writing a lot of math, and math is nothing but a series of transformations, called "production rules”, of “symbols”, which are subdivided as “terminal” and “non-terminal”. Loosely terminal symbols are items that the user can see as they are the outputs, whereas non-terminal symbols are the intermediate steps / states (“made-up things”). Based on the possible allowed symbol(s) - symbol(s) transformations we get a grammar. This grammar gives birth to different languages. We generally define non-terminal symbols in capitals like , terminal symbols as and string of terminals and/or non-terminals as .

Figure: This is an example of how to get string “ББББ” from the given start symbol “Ψ” by applying the given production rules. Use this diagram to understand what terminal and non-terminal symbols mean and how production rules can be applied to generate sequences. Image from here

When classifying abstract machines, one of the most simple distinctions is done on the number of operations it is permitted to perform. This limits the complexity of rules that can be executed on those machines. Noam Chomsky classified them on the basis of their capabilities that helped frame this entire subject, it is called “Chomsky’s Hierarchy” or “Automata Hierarchy” in "Three models for the description of language". Everything that a lower order machine can do can also be done by a higher order machine.

| Grammar | Languages | Automata The type of computer that can execute a program written in that language. | Production rules (constraints) | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-3 | Regular | Finite-state | (right regular) or (left regular) | Regular expression |

| Type-2 | Context-free | Non-deterministic pushdown | Programming languages and HTML or XML (+ everything Type-3) | |

| Type-1 | Context-sensitive | Linear-bounded non-deterministic Turing machine | Natural Language (+ everything Type-2) | |

| Type-0 | Recursively enumerable | Turing machine | ( non-empty) | Mathematics and all of logic (+ everything Type-1) |

Type 3 grammar (Regular) → These systems do not have any memory and thus can only tell if a certain pattern is being followed or not e.g. regex can find patterns but cannot tell how many times a pattern appears. The machines that can run this language are known as Finite-state Automata:

- A vending machine, where there is a clear order to be followed and the machine cannot go in any other state.

- Regular expression can only determine if there is a string match or not, it cannot tell the length or number of times some string occurs since it does not contain any memory.

Given a non-terminal input the output will always be either a terminal and maybe non-terminal.

Type 2 grammar (Context Free) → These languages have a superpower that they have a LIFO stack available to them which allows them to remember a few things e.g. it can detect when a parentheses was opened and closed or parse HTML / XML correctly. The machines that operate on these languages are known as Pushdown automata (PDA).

Generally speaking, this is how humans think of the logic that we have built. There is nothing more logical than nested math, and all programming languages are also defined at this level (python grammar spec, unofficial JS grammar). One homework every developer do tries once is to parse HTML using regex, and it does not work.

Type 1 grammar (Context sensitive) → These languages have a much more powerful memory, a tape. It can move around on the tape and change any value that they prefer. The length of the memory i.e. the tap is equal to the length of the input data, so in many ways this is a memory constrained version of a TM. The machines that operate on these languages are known as Linear Bound Automata.

In this grammar and output of any sequence depends on its neighbouring elements as well. It covers all the natural language semantics, just like this part of the sentence depends upon the words that came before the comma. Another example is Biological DNA sequences.

There is one specific rule for this which is that for a rule , . This is a critical differentiator between T0 and T1.

There are some problems that T1 can solve that T2 cannot solve e.g. (The Copy Language). A Type-1 machine can verify if a string is a perfect repetition of itself (e.g. abcabc). This is impossible for a standard Pushdown Automata because it can't "read" the bottom of its stack. We don’t use T1 over T2 though because it is computationally very expensive. If we want to detect in a program if a variable was declared before we process a line, we can just look up a symbol table instead.

Type 0 (Recursively Enumerable) → This describes all of mathematics, logic and algorithms. If Type-3 is a simple toy and Type-1 is a sophisticated calculator, Type-0 is a universal brain. In the theoretical domain we can distinguish between two “levels” of T0: Recursive language in which a computer looks at a string and eventually says Yes/No (Accept/Reject, True/False), but is guaranteed to stop. The other is where a machine looks at a string in a language and says “Yes” or it cannot find and say “No” or worse keep searching and never stop (we will come to this below).

The machines that operate in this language are Turing Machines. An important aspect of this language is that the output can be smaller than the input thus shrinking/deleting i.e. for a rule , it is possible unlike T1 grammar.

A classic example is the Language of Provable Mathematical Theorems:

- Imagine a language that contains every true statement that can be proven from a set of math rules (Axioms).

- A Turing Machine can start listing these theorems one by one ( , , etc.).

- If a theorem is true, the machine will eventually find it and say "YES."

- But if a statement is false or unprovable, the machine might keep searching through the infinite sea of math forever.

This last point is where we come across the famous Halting problem. Beyond this point are languages that Turing Machine can't even "start" to solve. These are called Non-Recursively Enumerable sets.

Congratulations it is 1956 and we are effectively at the “edge of the map”. But we need a giant calculator to go to the moon. However good in theory, we cannot build a Turing machine. We cannot provide a reliable, infinitely long magnetic tape and even if we could it would be a pain to program. We need to move from theory to practical computers that can be built.

I will cover it next.

References

- [4]Noam Chomsky (1956)

- [5]

- [7]

- [11]